Why supporting avoidance is not kindness

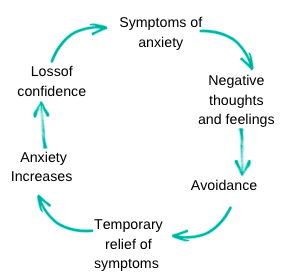

When children struggle with anxiety, it can feel like the kindest thing to allow them to avoid the situation that is affecting them. However, we quickly discover that the list of things that they need to avoid becomes bigger and bigger, and their world becomes smaller and smaller and smaller.

Safety Behaviours

When we use avoidance to manage anxiety symptoms, we call this a safety behaviour. Safety behaviours are temporary behaviours which alleviate the discomfort. Safety behaviours can be avoidance, distraction, checking or preparing. They are used to prevent fears from coming true.

- The discomfort of the anxiety creates a desire to ‘keep safe’ and so we will ‘avoid’ any trigger or stressor which creates an anxious feeling.

- In turn, this offers short term relief, reinforcing that avoidance is a positive strategy as the anxiety no longer presents itself.

- However, when we next experiences the trigger or stressor, the anxiety alert becomes stronger and more uncomfortable and we lose confidence in our ability to manage our anxiety and that strategies work.

- Subsequently, we can begin to feel that no strategies will be effective so their world reduces in size as the anxiety presents in more situations.

- The reduction in comfort zone increases anxiety in other areas.

Avoidance

Sometimes, avoidance is something that we have taught children, this is often unintentional, but may be:

- Because we use safety behaviours such as avoidance to manage our own anxiety

- That we find it hard to regulate our own emotions when children struggle so allow them to miss events / school

- That we believed that taking a day off would help the situation

- That the school have encouraged time out and we have followed advice

- That the school removed the child from class or provided an exit card but the child did not have strategies or resources to reacclimatise to the classroom

Zone of Tolerance

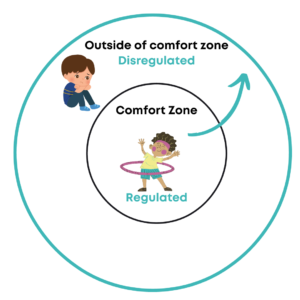

Within all of us is a comfort zone, the things that we feel comfortable being able to do. This is also referred to as our zone or window of tolerance (Dr Dan Siegel, MD). Each individual has a different size window of tolerance and as adults, offering children safe ways to expand their zone of tolerance is imperative to growth of confidence and resilience. Dr Siegel refers to our zone of tolerance as:

“the optimal zone of arousal for a person to function in everyday life”

In their zone of tolerance, child can manage their emotions and feel able to cope. However, when the zone of tolerance is small, the ability to function can become challenging as they are set into arousal in all areas outside of this. If you followed our previous article about the fight-flight response, we referred to this arousal (find it here).

Arousal can look different in every child, but can include:

- Anger

- Anxiety

- Fear

- Overwhelm

- Panic

- Hypervigilance

- Dissociation

- Depression / low mood

- Blankness

- Being empty / shutting down / unable to respond

Therefore, as adults, working with children to help them build confidence in expanding their zone of tolerance and allowing them to feel able to cope with new challenges is important to self-esteem, confidence, regulation and having quality life experiences.

Building confidence

In order to help a child grow their zone of tolerance we need to consider:

- Teaching children regulatory behaviours to support them to calm their nervous system (see link here)

- Teaching children somatic soothing activities to help them feel grounded (see link here)

- Creating a plan which builds children’s confidence slowly (small steps) to acclimatise to situations, this may begin with activities such as observing activities with a safe adult, having someone visiting classrooms with them, and building time up slowly.

- Build confidence and self-esteem by recognising achievements and using positive language which is compassionate to their situation and encourages children to see their growth.

- Finish activities on a positive, building up confidence in 5-10 minute intervals and leaving when things are going well so that the brain can develop a sense that ‘this is safe’.

- Implement stress release activities within the routine to prevent restraint collapse. This may include audios, regulation activities, activity or sensory based play.

- Be consistent in your approach – small steps which are repeated to build confidence are more important that big steps days apart. For instance, choose one step and repeat it until children feel comfortable, safe and confident rather than a big step which they feel a sense of failure if they cannot complete it.

- Where required, engaging with therapy to support children to manage their anxiety symptoms and where required, identify any triggers or negative experiences.

© Dandelion Training and Development – All Rights Reserved

Looking for more?

Don’t forget that you can register and subscribe to our newsletter to receive weekly articles and resources.

Further help

For more articles about mental health visit – HERE

To learn more about child and adolescent mental health visit – HERE

For resources to support child and adolescent mental health visit – HERE