Hypoarousal versus Hyperarousal

When we experience stress, we can have two different reactions:

- Hyperarousal – where we feel overwhelmed by the stress

- Hypoarousal – where we feel numbed by the stress

Any of us can become hyper or hypo aroused, however we frequently see these actions in children who are neurodiverse, such as those with autism spectrum disorder, sensory processing needs and attention deficit disorder (to name only a few).

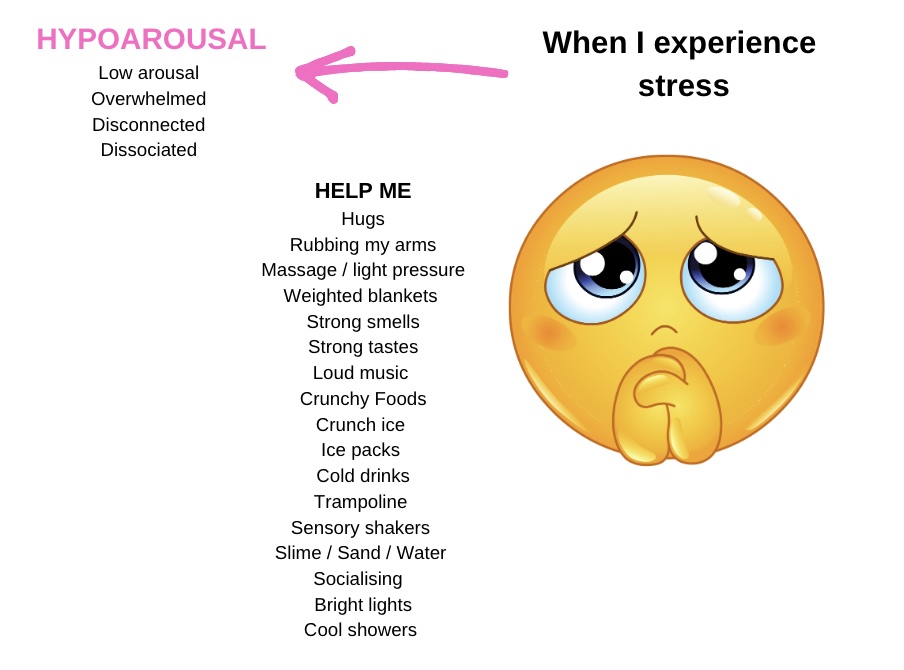

Hypoarousal

Hypoarousal occurs when we feel under-whelmed, it is associated with low arousal levels and can impact our sleep, eating habits, mood and energy levels, it can be described as:

- a ‘freeze’ response

- feeling numb

- feeling dissociated

- feeling frozen

- feeling like you are disconnected

- daydreaming

- brain fog

- exhaustion

- being very quiet or withdrawn

- socially isolating

- being unable to make decisions

- finding it hard to concentrate

- reporting having no memories of an event

When a child (or adult) experiences hypoarousal they can find it extremely difficult to alert others to their needs, and often become invisible, as they are not up-regulating or acting out to get attention that they are struggling.

Children who are hypoaroused, can be seen as sensory avoiding. Trying to reduce the input they experience and trying to decompress and regulate. However, this can look like they do not care, or are not interested. Children who are hypoaroused will frequently withdraw to decompress and reset their bodies sympathetic nervous system from the freeze response to the sympathetic nervous system (rest).

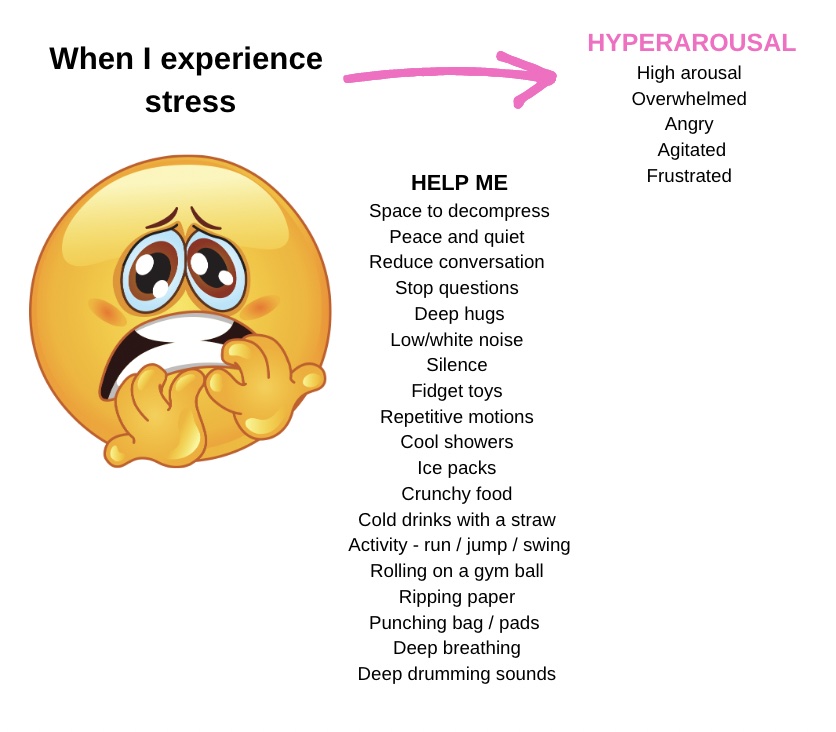

Hyperarousal

Hyperarousal is the other end of the scale, where a child (or adult) becomes overwhelmed by their environment. This can be from people, sensory input, situations, events or factors such as illness. Children who are hyperaroused, often are sensory seeking. They are looking to gain input to regulate.

Hyperarousal causes a child to feel overwhelmed and over stimulated by the environment. It creates the fight – flight response to be activated in the body. It can lead to symptoms and behaviours such as:

- agitation

- frustration

- irritability

- fidgeting

- trying to escape

- physical aggression

- anger

- risky behaviours

- hypervigilance

- unable to concentrate

- unable to communicate needs

- intruding on personal space

- constantly touching other people or things

- unable to sit still

- seeking out noise, colour or smells

- sensory seeking

- paranoia

- looking for risks / dangers

Children who are hyperaroused, up-regulate their responses to ‘tell’ us that there is a problem. However, this can frequently be mislabelled as poor behaviour. Hyperarousal tells us that the child’s nervous system is overwhelmed, and they will often tell us that they are not safe through words, actions or behaviours. They need support to decompress and regulate.

Note

Some children will move between hyperarousal and hypoarousal, impacted by different triggers, or combinations of triggers. Therefore, their strategies may vary depending on the situation.

How can we support?

We can support children by considering what they need – the best way to identify this is through conversation at a time when they are calm, children often, instinctively, know what they need.

Children who are aroused can be helped with a range of strategies, the core requirement is that we:

- Find their preferred strategies (these will be different for every child)

- Work these strategies into the day, not just at the point of overwhelm

- Implementing regulation time after busy days, or before busy events

- Considering what snacks and foods we add to lunchboxes to support at school

- Trial and testing to find the best combination

- Communicating so that all adults are aware of how to help

Strategies

- Co-regulating with a trusted adult

- Calm, quiet voices

- Remove any audience

- Breathing exercises

- Listening to music

- Crunchy snacks

- Cold drinks with a straw

- Ice packs

- Scents (e.g. lavender)

- Massage

- Holding a hand (if desired)

- Hugs (if desired)

- Safe spaces

- Quiet spaces

- Limit questions and conversation to reduce pressure

- Yoga

- Repetitive physical activity such as swinging, rolling, jumping

- Meditation

- Hypnotherapy

- Weighted blankets

- Play doh, slime or fidget toys

- Silence

- Naps

- Noise cancelling headphones

- Bi-lateral stimulation tracks

Want to learn more?

If you want to learn more about child and adolescent mental health, you can join our Level 4 training (here) or keep an eye out for our new specialist courses coming soon (here).

© Dandelion Training and Development – All Rights Reserved

Further help

For more articles about mental health visit – ARTICLES

To learn more about child and adolescent mental health visit – COURSES

For resources to support child and adolescent mental health visit –RESOURCES